Home » Posts tagged 'Emilio Aguinaldo' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: Emilio Aguinaldo

Marquardt Recounts Post-Landing Experiences, September 21, 1946

Marquardt Recounts Post-Landing Experiences

How he felt on returning to the Philippines on the heels of the retreating Japanese and his experiences subsequent to landing are told by Frederic S. Marquardt, formerly Assistant Editor of the FREE PRESS and now Foreign News Editor of the Chicago Sun, as part of an article written for the August number of “The Rotarian.” After declaring that World War II “destroyed the economic life of the Philippines” but that it “didn’t upset the independence timetable,” and giving a rapid review of event from Dewey’s landing to the Japanese occupation and the terrible destruction they wrought in the islands, he continues with what he describes as his—”HOME-COMING.”

September 21, 1946–I HAD the unforgettable experience of seeing at first hand what the Japanese had done in the Philippines and how the Filipinos had resisted. For I Also returned. I remember the day I landed on Leyte, and as I walked ashore on the beach on which I had played as a child, I kept repeating the words of what had once been the Philippine national anthem, “This is my own, my native land.”

That night I went around to Walter Price’s house in Tacloban, where General MacArthur had established his headquarters, to chat with his aide-de-camp, Larry Lehrbas. The General was pacing up and down the wide veranda, and as he saw me he came walking toward me, hand outstretched, and said, “Hello, Fritz. I’m glad to see you. Welcome home.”

It was home all right, for him as well as for me. I had gone there as an infant in my mother’s arms. In fact, I would have been born in Tacloban instead of Manila if there had been adequate hospital facilities there. And MacArthur had gone to Leyte as a “shavetail” fresh out of West Point. He has done his first campaigning on the nearby-island of Samar, where an insurrecto’s bullet had knocked his high-peaked hat off his head.

In a way, it occurred to me, the United States was also going home. Here in the Philippines American arms had suffered the greatest military defeats in their history, on those black days in 1942 when Bataan and Corregidor had fallen. And here now, on the full tide of such military might as the world had never seen, Americans were returning to liberate 18 million Filipinos as a necessary prelude to giving them their independence. In the future, the liberation of the Philippines and the redemption of the independence pledge would stand the United States in good stead, not only in Asia, but throughout the world.

A few days later I met Colonel Ruperto Kangleon, the Filipino guerrilla leader whose forces were harrying the Japanese rear while the American troops hit them from the front. “Are you related to the blue-eyed W.W. Marquardt who expelled me from the fifth grade when he was superintendent of schools in Leyte?” Kangleon asked me.

Back in Luzon

“Sure,” I said. “He’s my father. Were you a guerrilla then too?”

“Tell him to come back to Tacloban,” Kangleon said. “We’ll give a big banquete for him. We owe a lot to those American teachers.”

In Manila I saw 80 percent of the city pulverized and destroyed as the Japanese fought their senseless lastditch stand on the south bank of the Pasig. I attended the first postwar luncheon of the Manila Rotary Club in Gil Puyat’s furniture factory, miraculously saved from the flames. It was probably the only building in town that boasted 30 chairs.

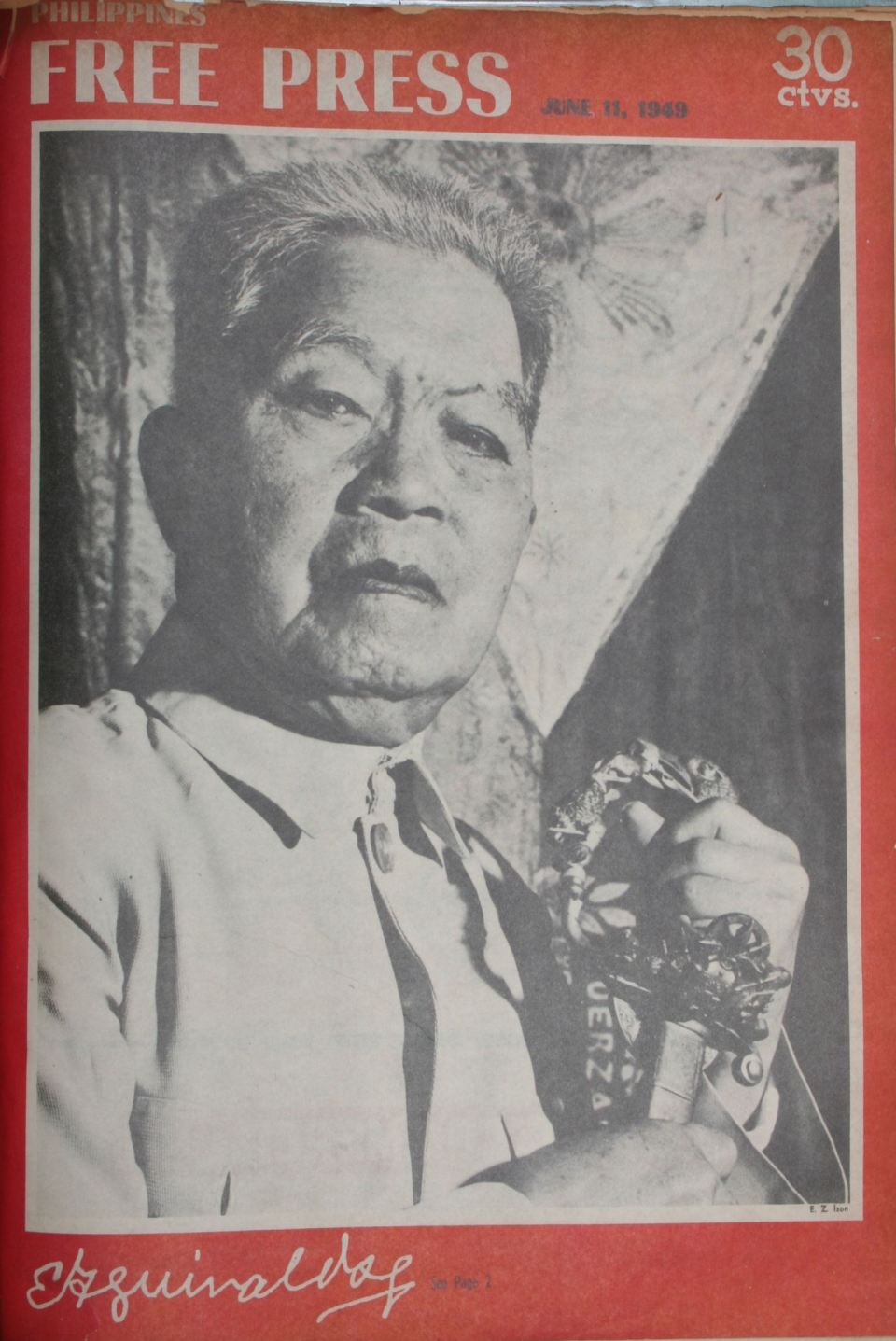

I even went out to Kawit to talk to old General Aguinaldo, who had fought the Americans so bitterly at the beginning of the American regime. During the Bataan campaign he had sent a message to MacArthur, urging him to surrender to the Japanese. After Manila had been liberated he had tried to see MacArthur and Osmeña, but neither of them would have anything to do with him. Now he sat among his autographed pictures of famous Americans, a simple old man who had been an ineffective pawn in the hands of the Japanese.

Determination

In many respects The Philippines was less prepared for independence in 1946 than it had been in 1898. The factories, the banks, the work animals, the transportation companies, the telephone systems, the power plants, the sugar and coconut and rice mills — almost the entire physical plant erected during the American regime had been destroyed. Then, after liberation, liberal spending by the American Army, in the absence of an almost complete lack of consumer goods, added a disastrous inflation to the other woes of the country. Although wages were doubled, the peso had a purchasing power of only one-sixth of its war value.

But the Filipinos had something more essential for the maintenance of independence than a going commercial and industrial plant. They had the determination born of scores of uprisings against the Spaniards; of long years of fighting against, and later cooperating with, the Americans; of the brutal injustices of the Japanese rule.

United behind Quezon, July 15, 1939

United Behind Quezon

July 15, 1939–“AYE!” With a tired roar that echoed hollowly in the dark bowl of the Rizal basketball stadium in Manila, one night last week, the Nationalist party convention approved the proposal to amend the Constitution, so as to allow the reelection of the President.

“Nay!” A half-hearted and scattered cry in opposition went up, after hours of resounding but futile debate.

An undisputed majority sent up an “Aye!” again, the following morning, approving another amendment, to revive the old senate.

The “Nay!” was even weaker.

For three days and nights last week, the party which rules the country met in the stifling shadow of a gathering typhoon to deliver itself of a series of historical mandates to its members in Malacañan, in the Assembly, in the cabinet, in every important office of the government. The mandates, expressed in resolutions, were to:

1. Change the Presidential term from one six-year period, to two four-year periods;

2. Revive the old bicameral legislature;

3. Create an administrative body to take charge of all elections;

4. Revise local governments to make them more, responsible and efficient (presumably, along the lines of the Quezon plan for appointive mayors and governors);

5. Readjust the three-year terms of assemblymen, provincial and municipal officials, so as to make them fit the new four-year presidential term;

6. Reaffirm loyalty to the coalition platform, including independence in 1946;

7. Request President Quezon to call a special session of the Assembly;

8. Ratify Presidential and Assembly action on the JPCPA report;

9. Congratulate President Quezon for his social justice program, and to request him to remain in office (that is, take advantage of the reelection amendment);

10. Congratulate Party President Yulo for his handling of the convention;

11. Increase the representation of governors in the Nationalist executive commission, from five to 12, thus putting them on a par with the Assemblymen.

The Sheep and the Goats

The convention was opened formally by Speaker Jose Yulo, in the afternoon of July 6. The morning had been devoted to the dry, and unexpectedly confused, routine of approving the credentials of the delegates. Every assembly district had been allowed three delegates, outside of the assemblymen themselves, and the provincial governors.

However, in many cases, the assemblyman and the governor concerned had not been able to agree on the delegates to be chosen, and had each appointed a separate set of three. This mix-up was unsolvable at the last minute, and the party heads decided to recognize everyone. Speaker Yulo, as president of the party, was reported to have signed the credentials of about 900, instead of the original 500, delegates.

But this large-scale hospitality had its limits. Efforts were made to exclude delegates known to be hostile to the amendment proposals. Paulino Gullas, a member of the 1934 constitutional convention, a delegate from Cebu by appointment of Assemblyman Hilario Abellana, faced ejection by party officials at the last moment. But the ouster had started too late; Gullas’ credentials had already been signed together with the others.

It was needless however to separate the sheep from the goats. The overwhelming majority of the delegates were under implicit specific instructions to vote in favor of the amendments. Several assemblymen opposed to the movement, among them Abellana, had not even bothered to attend the convention. The La Union assemblymen, reported to be antis at first, heatedly denied any convictions along that line.

Even Mrs. Cristina Aguinaldo-Suntay, the daughter of that stolid revolutionist and oppositionist, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, and herself a Popular Front candidate once upon a time, loudly proclaimed in advance her intention to vote for the amendments. Mrs. Suntay is a member of the Cavite provincial board; she campaigned for Manuel Rojas, the rebel Nationalist candidate for the Assembly, last year, and has apparently joined the now controlling Rojas branch of Cavite Nationalists.

The only opposition was expected from Lanao Assemblyman Tomas Cabili and his three delegates. Cabili, the only member of the constitutional convention who refused to sign the Constitution, apparently was now, by an ironic turn of fate, its sole defender.

So that when Speaker Yulo rose to address the convention at the end of the first day, he faced an audience that was in almost complete agreement with everything he was going to say, and he faced, beyond the audience, a nation which had almost always been in complete agreement with everything his party had said.

“The leaders of our party,” he read from a prepared script, “conscious of our duty and responsibility to the nation, have seen fit that at this juncture we should pause and evaluate the progress of our preparation for the day [July 4, 1946], and for the days that are to come thereafter, and decide whether under the surrounding circumstances, the political order that we have established can lend assurance to the accomplishment of the ideals so patiently and reverently waited for by our people.”

Such an evaluation, he continued, has “led our leaders to feel the necessity of the continuance of the present order, particularly as regards the leadership of the man who has laid the foundations of the Commonwealth government, and put into practice the new social justice policies enunciated in our Constitution. Unfortunately for us,” said the Speaker pointedly, “we are confronted by the provisions of our Constitution, which would not permit such an eventuality.”

“Conservative Reforms”

What was the Constitution doing? It “unnecessarily curtailed the right of the people to a free selection of the chief magistrate of the nation,” for it prohibited reelection of the President. It was “depriving the people of the right to change the chief magistrate for a long period of time namely six years, a period of time which, in the hands of an unscrupulous president, may lead the nation to decadence or destruction.”

The remedy? It was “the free and untrammeled exercise of the right of suffrage!”

Only one paragraph did the Speaker of the Assembly devote to the bicameral proposal, which would shear his house of half of its power. “And no less important,” he said, “is the necessity of guarding the nation against the possible onslaught of radical theories, now the preoccupation of many nations—and this can be met by effecting conservative reforms in our legislative body.”

The thunder of agreement that signaled the end of the party president’s exhortation forecast the quick approval of the “reforms.”

Next day however there was unexpected opposition. Cabili had announced he would not speak against the Constitutional amendments. But a foe, far more dangerous and eloquent than the Lanao assemblyman, one who had attacked presidential reelection long and loudly on the floor of the Assembly, had taken his place.

Leading the three delegates from his district, the fiery Batangas gamecock, Eusebio Orense, crowed a challenge. For two days, he and his three men, would strike many a sharp blow against the party leaders. And with him worked Gullas, annoyed by the attempt to oust him.

One of the Batangueños, former Rep. Rafael Villanueva, started the fireworks by challenging the legality of the convention. The delegates had not been appointed, he argued, as provided by the party rules—by municipal and provincial conventions. The objection was swiftly and irrevocably tabled.

Assemblyman Pedro Hernaez, smarting under a recent party snub, questioned the presence of Popular Fronters (Mrs. Suntay) in a Nationalist convention. Again the objection was buried.

The delegates scrambled over one another to file resolutions supporting the Constitutional amendments. A resolutions committee of 36 members, under Secretary of Justice Jose Abad Santos, had to be named to coordinate all these enthusiastic efforts.

“As A Free Man”

The committee reported out an omnibus resolution for the amendment of the Constitution with regard to reelection and the senate; the revision of local governments “with a view to making them more responsive to the actual needs of the people, thus rendering such governments more responsible and efficient”; and ratification of the coalition platform.

The party rebels made a brave show of speeches against the resolution, when it was submitted part by part to the convention, but they were crushed by a well-organized majority. Orense spoke in vain.

Villanueva denounced the reelection proposal as undemocratic and expensive; he sneered that the Assembly had started the movement in payment of President Quezon’s efforts for their reelection last year. So incensed were the legislators by this accusation that they persuaded the convention to strike Villanueva’s remark from the record.

Gullas gave the key speech for the rebels. “This is a free country. I shall speak and vote as a free man,” he began to a flutter of applause. “This resolution permitting the reelection of the President with a shorter term, with retroactive effect, is couched in general terms. The purpose is clear.

“This resolution is indeed a tribute to the leadership of President Quezon. I have voted for that leadership. I am following that leadership. But I shall vote against this resolution; for, in principle, I voted against it on the floor of the constitutional convention; because the constitutional precept prohibiting a presidential reelection was inspired by President Quezon, and the Constitution containing such prohibition was unanimously approved by that convention and overwhelmingly ratified by the Filipino people. I am voting against the resolution because I wish to be consistent with myself….”

FREE PRESS Poll Quoted

“Only a few days ago,” argued Gullas, “a straw vote conducted by the FREE PRESS, a non-partisan and widely read weekly in the Philippines was concluded. The result was against reelection. Of course, it is not an absolute indication of how the public will vote. But it clearly shows which way the wind blows. It is a barometer of the sentiment of the people. Like a finger on the pulse, it counted, as it were, the heartbeats of the nation.

“If that is not sufficient, two months ago, a debating team from the University of the Philippines toured the country from north to south, from east to west. The members of that team will tell you that in practically every town, the home team selected to defend the negative side of the question of presidential reelection. They will tell you that the public reaction in practically every city they visited was decidedly against the reelection of the President.

“What does it all mean? It means that the public wants you to give the Constitution a fair trial. They want the Constitution to reflect the stability, not the instability of our government; they want the Constitution to be permanent, and not transitory; enduring, and not reflecting the passing whims of the leader or party that may happen to be in power.”

The best heads and tongues of the party rallied to the defense of the amendment; sponsored on the floor by Assemblyman Jose Zulueta.

Assemblyman Pedro Sabido eloquently answered the argument that a second term might mean President Quezon’s death, by saying that the life of the nation was more valuable than the life of the President. Assemblyman Gulamu Rasul pledged the Moro people for reelection. But it took golden-tongued Manuel Roxas, drafted at the last minute, to swing the convention behind the proposal with cheering unanimity.

The vote on the proposal was by acclamation. Four delegates, however, were allowed to register dissenting votes afterward; all of them, Orense, Villanueva, Eusebio Lopez and Felipe Dimaculañgan, were from Batangas.

The rebels later denied that Yulo had invited all who had said “Nay” to put their opposition on record. Many who had raised a voice against reelection preferred to remain more or less unknown.

The party went quickly after the four marked men. Convention officials discovered that Dimaculañgan was not a bona fide delegate. Mayor Juan Buenafe of Batangas, Batangas, wired the convention: “The municipal council and the people of this town protest against the appointment of anti-reelectionist delegates. . . . We are unconditionally for reelection.”

Elections in 1939?

The reelection plan however seemed to have suffered a change. The old proposal was to hold the second election in 1941, when Mr. Quezon’s six-year term will be finished. He would then serve for two years of the new four-year term and then resign. However the plan now is apparently to hold the election this year, at the end of Mr. Quezon’s first four years, thus reelecting him for the full new four-year term.

The next morning, the convention took up the remaining resolutions, most important of which was the one on senate revival. Again Villanueva rose to object, supported by Iloilo’s Serapion C. Torre. The success of the unicameral Assembly, they argued was undeniable; why change the system?

But the only successful amendment to the amendment was one leaving the nature of the resurrected senate undecided; the President and the resolutions committee had advocated a senate-at-large. Other factions however wanted one senator for every province, or the revival of the old senatorial districts.

So headlong was the rush toward approval of the resolutions that Zulueta felt obliged to point out that the convention had no authority to change the Constitution; it could only suggest such changes to the Assembly or a constitution convention.

The Yes-men were in the immense majority, and when President Quezon arrived to close the convention, Saturday evening, he was greeted with a spontaneous roar. Moved by the demonstration, His Excellency repeated what he had told the Assembly in May: he was unwilling to serve more than eight years in all; he wanted to follow the precedent of George Washington.

He argued more at length on the need of a senate-at-large; it is believed, in fact, that one strong reason why Mr. Quezon is willing to go along on the reelection proposal is to secure the companion constitutional amendment for a senate.

But the strongest reason he gave at the end of his speech. “The only thing that I am afraid of,” he confessed, “is that after I leave the presidency the country may be divided, not along political lines, but on the choice of my successor. The country is not prepared for a great division among our people.”

There was indeed little fear of division as long as Manuel Quezon was President; the united tribute of the convention proved it once more. And if the Constitution is amended, the country need have no fear until 1943.

Only Garner can tell hearings’ outcome, August 20, 1938

Independence Merry-Go-Round

Only Garner can tell hearings’ outcome

By James G. Wingo

Free Press Correspondent in Washington

August 20, 1938–“WHAT do you think they are going to do now?” asked Vice-President Sergio Osmeña as soon as Sen. William H. King, acting chairman, announced that the Philippine bill hearings of the Senate committee on territories and insular affairs had ended.

He was not the only one asking that question. The patient Pinoy who sat in a corner for four weeks watching the proceedings open-mouthed also asked the same question. In fact everybody wanted to know that question’s answer.

The only man who can answer that question or any question arising on Capitol Hill is that prairie politician and sagebrush statesman, John Nance Garner, who today is the most potent political figure on the American scene. Filipinos may well remember this stubby, pinkish-whitish, bushy-browed, billikenish man who headed the large congressional delegation to Manila in 1935. Yes, this man knows the answer to the current Philippine question, but he won’t talk. Since he became vice-president of the United States in 1933 he has said practically nothing for publication.

So there’s no use running to Mr. Garner now although he granted me an interview once on the Manila-bound S.S. President Grant, which was promptly radioed to Manila. But the question must be answered somehow, as your correspondent is going to do forthwith, basing his answer upon the remarks of the committee members, their intonation when asking questions or making comments, their day-by-day attitude, their personal and political interests in the problem and many other things.

The interest in the Philippines shown by the committee members reflects that of the whole United States. It is a negative interest. The sentiment against being involved again in another war is so strong that even bold Franklin D. Roosevelt would not dare to buck it.

Many senators are afraid that the Philippines is a liability which may involve the U.S. in a Far Eastern war. As economic protector of the Philippines, what would the U.S. do if Japan grabbed an independent Philippines the way Germany grabbed Czecho-Slovakia? The U.S. would certainly be placed in a position to fight for a foreign country out of the orbit of the Monroe Doctrine, something which the American people are currently violently opposed to doing. If the Philippines were still U.S. territory, the American people would feel differently.

Today Congress would not grant immediate independence unless the Philippines asks for it, but outside the Emilio Aguinaldo crowd no Filipino seems to desire immediate separation from the U.S. For Congress to cut off the Philippines now would be universally regarded as a retreat in the face of the Japanese march of empire.

The American people want to retire from the Philippines as early as possible, but the U.S. government will see to it that the sovereign power retires gracefully. The Philippine Independence Act, whatever one may think of it, gives the U.S. a graceful “out.”

Naturally the average congressman would take the attitude, “Why disturb the whole thing? The Filipinos seem to be getting along all right under the act. Why not let the law run as it is?”

For both the U.S. and the Philippines, there are excellent points in non-action on the Sayre bill. This is not the proper time for the Philippines to ask for more economic concessions or economic changes in the independence act. True enough, the export taxes start next year, but the Sayre bill does not propose to eradicate the export taxes except on a few products, in which case the diminishing quota system will apply.

Shortly before 1946 conditions may change, and the U.S. may be in a mood to treat the Philippines more liberally. There is still this chance, this last thread of hope. But once the Sayre bill or part of it is adopted, that chance is lost forever. Forever is a long time, but it is reasonable to use the word in this case.

Some seasoned observers of the situation believe that rather than let all these long hearings go for naught, congress may adopt the part of the Sayre bill pertaining to the remainder of the commonwealth period. This portion affects only coconut oil, cigars, scrap tobacco and pearl and shell buttons. Resident Commissioner Joaquin M. Elizalde described the proposed changes embodied in the Sayre bill as “of the greatest importance to our economic stability during the second portion of the commonwealth period, 1941 to 1946.”

But almost everybody here is of the opinion that extending U.S. economic protection to an independent Philippines until 1960 is something congress will not do—at this time. Congress reflects the attitude of the American people much more than the U.S. President does. And today the American people are strong for isolationism.

Of course, don’t take all this as pure gospel. Only “Cactus Jack” Garner knows what Congress will do. And he won’t talk!

So your correspondent will continue where he left off two weeks’ ago—continue to give a faithful account of the hearings. As an intelligent reader, draw your own conclusions and make your own predictions. On this question you have as much chance of hitting the mark as any of us here.

After reading his splendid brief, Commissioner Elizalde told the committee not to get the false impression from Severino Concepcion’s testimony that the “Philippine Federation of Labor,” which he represented, was a mighty organization like the C.I.O., despite its imposing name. The commissioner also informed the committee that the President of the Philippines has established

a minimum daily wage of one peso in all industries, including sugar.

“Taken in the light of American wages, this is very low, but it is the highest ever paid in the Islands,” he said. “Furthermore in a great number of our products, we have to complete with other tropical countries which pay very low wages. We cannot raise wages as we would like to.” He also pointed out that Filipino wage-earners usually get free housing and medical treatment.

Following Commissioner Elizalde, Missioner Osmeña personally took the stand for the first time. Dressed nattily in a grey suit, he read a prepared statement, intended to clarify the commonwealth government’s position.

He categorically averred that “the conformity of the Philippine government to this bill represented the permanent views of that government.” He explained the use of figures showing “that during a 50-year period Philippine purchases of American goods registered a higher percentage of increase than American purchases of Philippine goods” as primarily “to indicate the value of this trade, to portray its possibilities, and to serve as documentation…that the economic problem involved in the political separation…is one of tremendous proportions.”

Expressions of gratefulness appeared many times in Commissioner Elizalde’s statement. Mr. Osmeña reinforced them with this:

“The Filipino people have always been pleased to recognize that they have derived great benefits from the free admission of Philippine products into the United States. Previous Philippine missions have frankly and openly admitted this fact. An expression of this sentiment has been reiterated and placed in the record of the proceedings of this committee in the cablegram sent by the President of the Philippines. The sense of gratitude of the Filipino people is strengthened by the knowledge that those responsible for the initiation of the free trade policy between the two countries were animated by altruistic motives….

“And the Filipinos further believe that the gratitude they owe to the American people cannot be measures solely by the economic benefits….America brought to the Philippines the spirit of free institutions, and, in accordance with the spirit, she prepared the Filipino people for self-government. She gave to the Filipinos ungrudging assistance in transplanting to Philippine soil the blessing derived from modern science, technology, and culture,” etc., etc.

McDaniel’s statement

There was no doubt now that President Quezon’s “gratitude” cablegram was compelled by cabled reports of Missioner Razon’s answer to questions made by inquisitorial senators. In his remarks Mr. Osmeña pointed out that he was clarifying statements made during “the discussion concerning my statement of the views of the Philippine government.” It may be remembered Mr. Razon read the Osmeña statement and answered questions for the chief during the illness of the Missioner No. 1.

The chairman of the Cordage Institute, astute J.S. McDaniel, followed Mr. Osmeña on the stand. Said he, “In view of Mr. Elizalde’s remarks this morning, there is nothing left for me to say. I merely want to place my statement in the record.”

Really, with Mr. Elizalde’s acceptance of the Cordage Institute’s amendment to the omnibus bill (an extension of the present Cordage Act to 1946) in an answer to perspicacious Chairman Millard E. Tydings’ inquiry, there was no need to say anything further. In his prepared statement Mr. McDaniel pointed out the existence of the mutuality of interests between the Philippine people and the U.S. hard fiber, cordage and twine industry. He recalled how the Cordage Act came into being—through a compromise between Manuel Quezon (then Philippine senate president) and the Cordage Institute with the approval of certain members of congress. He termed Francis B. Sayre’s calling the Cordage Act “an unfair discrimination against those islands” an “erroneous conclusion.”

“Americans are particularly disturbed over the possibility of Filipinos’ shipping rope yarns into the United States in the form of binder twine, which, under our customs’ policy expressed in our laws, as we understand it, cannot be prevented,” he declared. “Two-thirds of the manufacturing processes of the finished produce—preparing the fiber and spinning the yarn—would be completed by cheap Oriental labor. The practical effects would be the same as if there were no quotas, limitations or tariffs on Philippine hard fiber products coming into this country….

“Certainly there is no ‘imperfection or inequality’ in preventing the Philippines from creating a new industry based on an American market already harassed by prison and foreign competition. If the Philippines were to usurp any part of the binder twine market of the United States, that would force United States manufacturers to find some use for their manufacturing capacities. In turn, this would bring about excessive competition in rope sales, depressing values, which would depress the prices of the Manila fiber (abaca)—so important to Philippine economy.”

Senatorial interest in the hearings reached a new low on the ninth day. Today only Mr. Tydings was present to listen to the most hysterical witness of the entire hearings—and perhaps in any hearings on Capitol Hill in recent years.

Chairman Tydings warned today’s witnesses: “Don’t go over ground already covered, for if you do so, we will not have any bill acted on before the Fourth of July.”

The hysterical witness was notorious Porfirio U. Sevilla, the publisher of the scurrilous Philippine-American Advocate, which has discomforted many famed Filipino politicos, especially President Quezon, Quintin Paredes and Commissioner Elizalde. The resident commissioner was absent today, but Missioner Osmeña and Camilo Osias saw this pompous Pinoy strut his stuff.

Dressed handsomely in a well-tailored grey suit, red-and-grey necktie and black-and-grey shoes, little Porfirio Sevilla strutted to one end of the committee table and promptly started banging it. “I am appearing against this bill for three cardinal reasons,” he shouted. “First, it is legally questionable whether congress can repeal or amend the Philippine Independence Act.”

The second and third “cardinal reasons” were lost in the subsequent hysteria which made it almost impossible to understand the speaker. The remarks he made before Senator Tydings are lost to posterity because the official stenographer could not follow him. He merely made this notation, “Unreportable.”

“Don’t be funny!”

While little Porfirio huffed and puffed, Mr. Tydings went on sucking at his cigaret holder, saying nothing. Even when the witness shrieked, causing consternation in the halls of the huge senate office building, the senator did not change his Mona Lisa countenance. People in other offices kept calling the Indian Affairs committee room, in which the hearings were now being held, to find out what was going on. Some thought a wild Indian had gone on the warpath.

“Quezon is coming down here again to ask for some changes in the Independence Act,” the runty Pinoy screamed. “The congress should not allow him to do so.

“All our industries are under the control of foreign interests,” he thundered next. “Let’s have the independence you have promised us—because we want it.”

Changing his voice to a sarcastic intonation, he stated, “We are coming here to ask changes, Mr. Chairman, because we are afraid of the Japanese. The Japanese are going to get us! Ha! ha! Oh, Mr. Chairman, don’t be funny.”

Mr. Tydings was now reading the Congressional Record, and did not even look up at the speaker.

“I want to emphasize the principal point,” Sevilla vociferated. “Filipinos are expecting independence in 1946. Only 25,000 Filipinos will be affected by this pending bill. How about the others? They don’t know anything about it. They only know that they will be free in 1946.

“You will be blamed, Mr. Chairman, if you will pass this bill. This is no practical joke. You will be blamed if you pass this bill.

“The Filipinos do not know the meaning of this bill. They do not know that they will be tied up until at least 1960. I warn you, Mr. Chairman, there will be a civil war if you pass this bill.

“The Filipinos believe in you, Mr. Chairman. The ratification of the Tydings McDuffie Act by my people was a blessing. And let me remind you that if you extend the Act to 1960 my people will revolt against the sponsors of this bill.”

Report unread

Then busy Porfirio mentioned that only a very few people in the Philippines could read the report of the Joint Preparatory Committee on Philippine Affairs, upon which the Sayre bill was based. He brought up the problem of the Pampanga sugar workers. “They are mistreated,” he shrilled. “They are oppressed. They are getting only 20 centavos a day.”

He told the committee or rather Mr. Tydings that he had just received a cablegram, which read, “Do not testify.” “Mr. Chairman,” roared the witness, “do you think I am the man to be bribed! Don’t be ridiculous.”

If Mr. Tydings had heard that remark, he presumably passed it up as coming from a hysterical person unable to speak coherently, to speak grammatically or to weight the meaning of his words, for the senator continued to read the Congressional Record. When witness Sevilla failed to get the attention of the senator with his screaming and table-pounding, he resorted to imagining voices. “Mr. Chairman, I beg your pardon. I didn’t get that.” Mr. Tydings had said nothing, so the audience guffawed, but the senator remained immovable.

Sevilla mentioned several U.S. national heroes, and then he bellowed, “I am willing to defend my people to my last drop of blood. Don’t be misled by so-called Filipino patriots. By any means, go to it, Mr. Chairman.

“President Roosevelt was misled by the JPCPA. This bill was planned in the Manila Hotel, where the members of the JPCPA had a good time. You can’t get a true picture of the Philippines that way.

“I appeal to you now. Please give our independence in 1946. There will be a revolution if you don’t do it.”

Such a witness as Porfirio Sevilla would undoubtedly not last one minute before a Philippine National Assembly committee if he would be allowed to appear at all. But in the U.S. conception of democracy, this fellow had as much right to say what he wanted as Sergio Osmeña or President Quezon. Mr. Tydings permitted the witness to bellow until he was exhausted. When the witness stopped fulminating, the senator said, “Thank you, Mr. Sevilla. Who’s next?”

Next was J.M. Crawford, manager of the Philippine Packing Corp., a 100 percent American-owned pineapple company in Mindanao, which started investigating the field in 1921, planting pineapples in 1928 and canning in 1930. The company is now canning more than half a million cases annually and practically 100 percent of this is shipped to the U.S., according to Manager Crawford.

On behalf of U.S. interests

“We followed the American flag to the Philippines not as philanthropists to spread American industry or to improve conditions for the Filipinos but to make money for ourselves,” testified Mr. Crawford frankly. “To date we have not recovered our investment. We have however assisted in developing an American industry. We have also definitely assisted the Filipinos, particularly those living in northern Mindanao…. We have found the Filipinos to be good, conscientious, loyal employees, who like the Americans and are grateful to the United States.

“We would like to have Senate Bill 1028 become a law for this would give us more time to recover and make a return on our investment. I have no authority to speak for other citizens of the United States living in the Philippines but I believe the position of my company is typical of other American investors in the Philippines.”

Two other senators, John E. Miller and Bennett Champ Clark, showed up, while Mr. Crawford was speaking, to reinforce the lone Mr. Tydings.

After Mr. Crawford there was nobody else on the docket for the day. The chairman wanted to know whether there were some more who wanted to be heard. Vicente Villamin stood up and said that he would like to speak the next day.

“Why not now?” asked Mr. Tydings, and the best known of all U.S. Filipino economists pulled out his prepared statement, walked to the large table and began giving the defects of the pending measure. Said he:

“The first defect is this: The bill sets forth a plan of a limited, declining preferential trade between the United States and the Philippines from 1946 to 1960. This plan is to be incorporated in an executive agreement. This agreement is made immune from denunciation for seven years. But…it is subject to revocation on six months’ notice…. The effect of this provision is to deprive the Philippine government of the treaty-making power which it should acquire automatically with the assumption of independent sovereignty….

Villamin’s contentions

“The second defect is this: The plan of trade dissolution, euphemistically called a readjustment program, will take the form…of an executive agreement between the President of the United States and the President of the Philippines. The pertinent provision of the bill gives the former only permissive, not mandatory, authority to enter into such agreement…. There is no reasonable or rational certainty that there is going to be any agreement at all when the fateful year of 1946 rolls around….

“Two questions arise: Firstly, would not progressive disintegration of the Philippine-American commerce…be more painless to the Philippines than its abrupt cessation…in 1946? My answer is this: It is preferable…to have five years more of the existing free trade arrangement of no tariff duties and no declining quotas and trust not only to the magnanimity of the United States but also to the eventual recognition of the relative value of Philippine economic potentialities for a new deal for the period after 1946….

“Secondly, what is a reasonable alternative to the bill? My answer is this: Let congress proceed to repeal the export-tax provision of the Tydings-McDuffie Act…. The provision is unnecessary now. According to the report of the Joint Preparatory Committee, the Philippine net bonded debt in 1946 will be but approximately $21,000,000. Today the Philippine government has a cash surplus six times that amount.”

The committee disposed of Mr. Villamin without asking him a single question. The senators seemed to be thinking of anything but the Philippines.

John J. Underwood, representing the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, was the first speaker on the tenth day. When he began reading his statement he had three senators to listen to him—Tydings, Arthur H. Vandenberg and Key Pittman. Also present were Missioner Osmeña and Commissioner Elizalde.

“A committee of the chamber has studied the bill under consideration,” Mr. Underwood droned, “and has reached the very definite conclusion that any premature change in the economic relationship between the United States and the Philippines, without opportunity for adjustment, will result in chaotic and unstabilized conditions to the great detriment of the United States as a whole, and in particular to the Pacific Northwest.

“One-third of the exports of the Northwestern area to Asia are marketed in the Philippines. The citizens of Seattle are now negotiating with the Maritime Commission a proposal to establish a new American line of steamships on this essential trade route. Many thousands of dollars have been spent by Northwest business enterprises in building up trade at Manila and other points in the Far East and this money was expended in anticipation of permanent trade relations with the Islands and on a basis of favor of competing with other countries for this business….

“It is the belief of many Pacific Coast businessmen who have been close to the situation that the American interests who are proponents or who lobbied on behalf of the plan to abrogate the present preferential trade agreement between this country and the Philippines had but one object in mind. It was not philanthropy which influenced their sentiment on behalf of the Philippine people to give them their right to self-government; their purpose was to convert the status of the Philippines into a foreign country…. These interests reason that any barriers against Philippine imports will place similar products from Cuba on a preferential basis in entering the United States.

Pacific Northwest interests

“The proximity of the Atlantic Coast to Cuba naturally gives that section a greater interest in Cuban trade than in the Philippines. These Atlantic Coast interests fail to realize that the Pacific Coast as a part of the United States of America is entitled to share the benefits of this country’s trade with all sections of the world and should not be discriminated against in favor of other parts of this country….

“The State of Washington has considerable interest in any national or international policy agreed upon which will affect the trans-Pacific trade of this section of the United States. The exported products are the very life of the United States Pacific Northwest industries and include lumber, flour, fruits, vegetables, dairy and poultry products, canned salmon, condensed milk, paper, pulp, mill and mining machinery…. The proposed new American steamship service which contemplates operating out of Seattle to the Philippines and trans-Pacific countries is dependent upon the inbound and outbound cargo from and to that country for its regular service. Continuation of preferential trade relations…is essential to those industries, for if a policy between the two countries is established upon a non-preferential basis it will mean absolute elimination of a large percentage of our exports and this trade will revert to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan and other countries…. Foreign shipping lines…would be stimulated by this direction of trade at the expense of…American lines….

“For the reasons stated we respectfully urge this committee favorably to report S. 1028 now under consideration.”

Mr. Underwood’s handsome grasp of the Pacific Northwest situation as it would be affected by the Sayre bill evoked a mere “Thank you” from the committee. It was unfortunate for the Sayre bill that Washington’s Homer T. Bone was not present to listen to the arguments propounded by Seattle businessmen. Mr. Bone had not acted friendly at all to the Sayre proposal.

Herman Fakler, vice-president of the National Millers Association, the national trade organization of the U.S. wheat flour milling industry, reinforced the Pacific Northwest’s opposition to “the abrupt elimination of trade relations” between the U.S. and the Philippines, as voiced by Mr. Underwood. “We do not feel that it is economic to liquidate our present trade relations,” he said, “but rather that we should endeavor by some means to preserve our existing trade.

“Our principal competitors in wheat flour in the Philippines are Australia, Canada and Japan. The elimination of preferential treatment for American wheat flour, therefore, would merely mean handing over our very valuable trade…to our competitors….

“The Philippine market…is of great economic value to the wheat growers of the Pacific Coast. It offers an outlet for their surplus wheat…. Therefore, we favor the objective of the bill now before your committee.”

Astute Senator Vandenberg elicited the information from Mr. Fakler that the flour sent to the Philippines is subsidized by the U.S. government at about $1 a barrel. “You would be more interested in the subsidy than in long-range planning for Philippine trade,” the senator crackled. “You wouldn’t need this bill if you had the subsidy.”

“But we don’t know if the subsidy will continue,” replied the witness.

“That’s right, you don’t,” shot back Mr. Vandenberg, who may become the next U.S. President and who, if elected, will surely scrap many of the New Deal projects which are now costing U.S. taxpayers plenty of money.

U.S. citizenship for Pinoys

V.N.P. Zerda, Filipino lawyer in Washington, proposed an amendment to the Sayre bill providing for U.S. citizenship for Pinoys married to U.S. women and who have lived in this country since May 1, 1934. However, he made excursions to many other subjects.

He mentioned a book which purported to say that beet sugar “smells bad.” Promptly the senator from a U.S. beet district, Mr. Vandenberg, growled, “What did you say about beet sugar?” The witness replied that he was quoting a book.

“The book smells worse,” the senator said.

Witness Zerda continued to read his statement: “The most sorrowful of Filipino life in this country comes when he knows that he is not a citizen of the United States and cannot become one….

“I also heard…here last Thursday that England takes good care of the English anywhere in the four corners of the globe. I happen to know that England takes good care of her colonies, as well…. If there is democracy at all it is in England….

“There has been a saying that if you can save a soul, nothing else matters. Gentlemen of this honorable and distinguished committee, your just and equitable appraisal of Filipino rights, privileges and preferences would save you a great race of people who have already proved to you to be worthy of erecting a monument in the name of American Western civilization, in the name of Ferdinand Magellan.”

In the name of Ferdinand the Bull, I wish I could end the account of these hearings this week and get to doing something else. But we still have to take up “Gold King” John Haussermann, who made a stirring plea for kindness to the Filipinos; that “garrulous general,” William C. Rivers, who kept committee members splitting their sides with laughter; grand, old Harry B. Hawes, who took up two hours to say what he admitted could have been boiled down to a few minutes, and two or three others. So then until next week!

Coalition ticket wins by landslide, September 21, 1935

September 21, 1935

Coalition ticket wins by landslide

Quezon and Osmeña carried into office on huge wave of votes—even Manila votes for Senate President:

Burying all opposition under an avalanche of votes, the coalition ticket of Manuel L. Quezon for president and Sergio Osmeña for vice-president on Tuesday overwhelmingly won the first national elections ever held in the Philippines.

Although the victory of Quezon and Osmeña had been a foregone conclusion, even their closest followers were surprised by the coalition strength shown in such bitterly contested districts as Manila and Cavite, where General Aguinaldo was expected to show the most strength, and in the Ilocano provinces, where Aglipay was admittedly at his best.

Osmeña leads all

In Manila, where minority leanings have always been pronounced, Senate President Quezon polled a total of 25,454 votes to Aguinaldo’s 10,236 and Aglipay’s 4,503. In many towns in Cavite where it was expected that the general would walk away with the honors, the coalition ticket ran neck-and-neck with the favorite son. In Ilocos Norte Bishop Aglipay had things all his own way, but in other Ilocano provinces it was a nip and tuck fight. In the Visayas the coalition ticket ran ahead of the opposition, although in some of the Bicol provinces Aguinaldo was showing strength on the face of early returns.

But it was not Senate President Quezon who received the most votes in Tuesday’s election. It was Senator Osmeña, coalitionist candidate for vice-president, who ran well ahead of his running party, largely due to the ineffective candidates presented against him.

Although fear of uprisings and disturbances could be noted on every hand previous to the election, no official word of any serious disturbances was received on election day.

Extreme vigilance on the part of police and constabulary, in addition to the heavy rains which fell throughout most of Luzon on election, was held responsible for the quietness which prevailed everywhere.

In his Pasay home the future president of the commonwealth received the election returns as rapidly as they could be gathered. When it became certain that he had been elected, Mr. Quezon issued the following statement:

“I am overwhelmed by the result of the election. I am more than grateful to my people for their generous support and confidence. The thought uppermost in my mind now is the great responsibility that this election entails. With God’s help I hope I will not fail my people.

“The results of the election show our people have placed their faith in the platform and men of the coalition. The Filipino people expect us to build the firm and solid foundation of the Philippine republic.

Aglipay in cinema

“In this hour of triumph I am thinking only of the great task before me and I seek God’s help to meet the grave responsibilities that have been placed upon my shoulder by my election as the leader of this nation.

“My heart goes in deep gratitude to my people who have so generously honored me.”

The results were a severe blow to General Aguinaldo who had issued a statement on the eve of the voting declaring: “Whatever may be the results of the election, I trust that the will of the majority will be respected.” Following the tabulation of results, the general said: “It is incredible…electoral manipulations….My duty to the public has not yet been terminated.”

Bishop Aglipay, unworried by the election results, attended a Manila cinema alone on election night. When the returns were in he sent a telegram congratulating President-Elect Quezon.

End

The Vital Question, February 11, 1933

February 11, 1933

The Vital Question

BACK and forth across the length and breadth of the Philippines, tossed upon an apparently endless sea of speeches, the question of whether to accept or reject the Hawes-Cutting-Hare independence bill was discussed from every possible angle this week. And still there was no definite decision, still the political bosses and the intellectual leaders were divided into two opposing camps, still the people pondered upon the greatest decision which any country could possibly be called upon to make.

The main point of dissension between those supporting and those opposing the bill was whether or not it really provided independence. But in answering that question such a mass of relevant and irrelevant matter was raised that the public began to wonder what it was all about.

The most monumental event of the independence week was the wordy battle between those two staunch deans of the University of the Philippines, Maximo Kalaw and Jorge Bocobo. Their articles are reported in brief beginning on Page 28 of this issue.

The most significant event of the week was the definite stand against the bill taken by Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, president of the short-lived Philippine republic, who presided over the annual convention of the Veteranos de la Revolucion in the Manila stadium Sunday. Asserting the bill was “the outcome of the efforts since 1930 of moneyed American and Cuban interests in sugar and other industries,” the old general declared:

Aguinaldo’s opinion

“The Bill imposes conditions that would work untold hardships upon our people, aside from the fact that it is not certain whether at the end of the 10-year period our independence would actually be granted us. About the only thing that appeals to us in this Bill is the grant of independence which is the goal of our people and for which we are sincerely thankful to America. Aside from this, however, the Bill spells an incubus on the shoulders of our people.”

Two courses of action were recommended by General Aguinaldo: “To amend the Hare-Hawes-Cutting bill or to ask a better bill from the ensuing Democratic administration and congress.” He feels that “from the incoming congress a more liberal independence bill may be obtained.”

However, the convention took no action either to approve or disapprove the bill, following this sage counsel from their president: “Let us proceed with caution, my comrades and countrymen, and let us not all too hastily give our answer to the question upon which depends the destiny of our people. Let us study its provisions further and meditating over the history of our country and that of America, let us look for what would redound to the glory of our land.”

Be Prepared

Finally, General Aguinaldo enjoined his comrades in arms to be prepared for a special assembly in case the legislature attempted to take precipitous action on the question “If the legislature,” he said, “should resolve to decide before the return of the Mission, it would be our duty to make known our decision before the legislature acts. In view of this, you are requested to vote finally on the question at an extraordinary general assembly of which you will be advised in time.”

In addition to General Aguinaldo, opponents of the bill found another recruit in the person of Sen. Claro M. Recto, leader of the defunct minority party in the senate. Declared Senator Recto in Iloilo: “The bill is so bad that we cannot obtain a worse one.”

The most startling declaration during the week was made by Prof. Melquiades S. Gamboa, of the U.P. college of law. A pundit who has studied law at Oxford, he declared that the Hawes-Cutting-Hare bill “is already a law” and hence already in full effect, regardless of the Philippine people or their representatives. The basis for his argument was the belief that congress had no constitutional right to refer the law to the Philippine legislation or to a special convention for ratification.

Proponents of the bill received more and comfort from U. P. President Rafael Palma, one-time member along with Quezon and Osmeña of the “Big Three” of Philippine politics. Categorically and explicitly, he declared, “The time has come for the country to change its leadership. We need new direction and new guidance.”

Since it has been bruited about that President Palma would resign as head of the university in order to reenter politics, the university faculty unanimously passed a resolution “expressing its full trust and confidence in President Palma and its wholehearted support of the continuance of his administration.” Said Senate President Quezon, “There is no reason why President Palma should resign.”

In the legislature interest was centered largely upon the fortunes of Floor Leader Francisco Varona, whose opponents attempted to take from his leadership, since he was unwilling to define his stand on the independence bill. Failing to secure the necessary number of votes to oust Representative Varona, a caucus of lower house members offered to send him to the United States along with Senate President Quezon, then proceeded to elect Rep. Jose Zulueta to act in his place should he go. Said Senate President Quezon, “I have no right to invite Representative Varona or anybody else to go with me and I can say that I have not done so.”

But Manila no longer held the center of the stage in the independence parleys this week. In Cebu a monster mass meeting on Saturday night protested against the Hawes-Cutting-Hare bill, and passed a resolution expressing “its condemnation of the work of the Philippine mission in Washington which ignored and disobeyed the instructions of the Philippine legislature and the Philippine commission of independence.”

Senate President Quezon in several public speeches said: They are at the foot of the mountain and I am far from it. What is happening with the mission is what happened to me when I was for for the enactment of the Jones bill. The only difference is that I have experience and I cannot be fooled for the second time. I was gullible once when I was dazzled by the beauty of the preamble of the Jones bill and I failed to notice that the independence promised me by Congressman Jones was not in the law itself. The mission is now dazzled by the fixed date promise of independence and is holding to it as tightly as I held to the preamble, ignoring the other provisions of the law.”

Concerning himself the senate president said:

“Let me tell you that from a purely personal viewpoint it is foolish for me to object to the acceptance of the Hawes-Cutting act. If I were politically ambitious, there is nothing better for me than to advocate that it be accepted. Given the power that I am now represented to have, if I favor the acceptance of the Hawes-Cutting law and it is accepted by the people, I can have myself elected the first governor general of the commonwealth even by using the means resorted to by Ex-Representative Garde since, under such a law, aside from the American interests, it will be only the one fortunate enough to live in Malacañang that will be benefited by it.”

From the United States came only one significant pronouncement, the declaration by Sen. Key Pittman that the Philippines would have to accept the bill in its entirety or not at all. There could be no “acceptance with reservations,” as so many conservative Filipinos have suggested, according to the senator from Nevada. He said further that the compromise plan embodied in the bill was the inevitable solution of the question.

Sumulong To Run For Senator, August 4, 1925

Sumulong To Run For Senator

Election Postponed to October Two, Registration September Thirteen, Mission To Leave for America Shortly

HIS home stormed by an enthusiastic throng of Democratas, Judge Juan Sumulong was carried aloft on their shoulders through the streets Thursday evening, and in a stirring address at Plaza Moriones, Tondo, told the crowd of over 3,000 supporters that he would be a candidate for senator in the fourth district.

His acceptance came after a week of pleading on the part of Democrata leaders, but he steadfastly refused until the popular demonstration of Thursday evening. The election will be held October 2, the date having been changed from August 23 at the request of the governors of all the provinces concerned and the mayor of Manila. All those who did not vote in the last election must register on September 13.

Since Judge Sumulong has accepted the nomination, the negotiations between the leaders of the two parties to nominate General Emilio Aguinaldo as the joint candidate of the two parties have fallen through.

Coalition Bitterly Arraigned

At Thursday’s Democrata meeting the principal speakers were Governors Cailles and Montinola, Senator Tirona, Representative Mendoza, and Judge Sumulong. They bitterly arraigned the coalition leaders on their conduct of the government, especially of the independence campaign, saying that independence funds had been used for junkets to the United States.

Judge Sumulong, in accepting the nomination, delivered a long address defending his acts while Philippine commissioner and stating that the coalition were opposed to his ever becoming an elective officer because he could expose their misdeeds. “I wish to state frankly here,” the candidate said, “That I decided to quit politics and retire to public life, not because I shun the public service but because I wanted to escape the insults of those of the other party.”

“Waterloo is Coming”

“The Waterloo of the party in power is coming. Its death is sure, it is inevitable.” He called the Wood-Quezon clash a trap to get votes, and said that “the people are wise now. Even though Quezon and Osmeña put on masks the people can see through them.”

The coalition have also been busy during the week, their leaders having campaigned in Laguna province and in Bataan, in addition to their Monday night meeting in Manila. According to them the candidacy of Mr. Fernandez was everywhere received with acclaim.

Orators Going to U.S.

It is now stated that neither Quezon nor Osmeña will head the mission to present the Filipino side of the present crisis before the American people. Speaker Roxas is expected to go, however, and he will be aided by a corps of eight well-known orators and publicity men, including Dean Jorge Bocobo, Camilo Osias, Eulogio Benitez, Jose P. Melencio, Carlos P. Romulo, Dr. Gaudencio Garcia and Victoriano Yamzon.